About The Appalachian Hiking Trail

About The Appalachian Hiking Trail

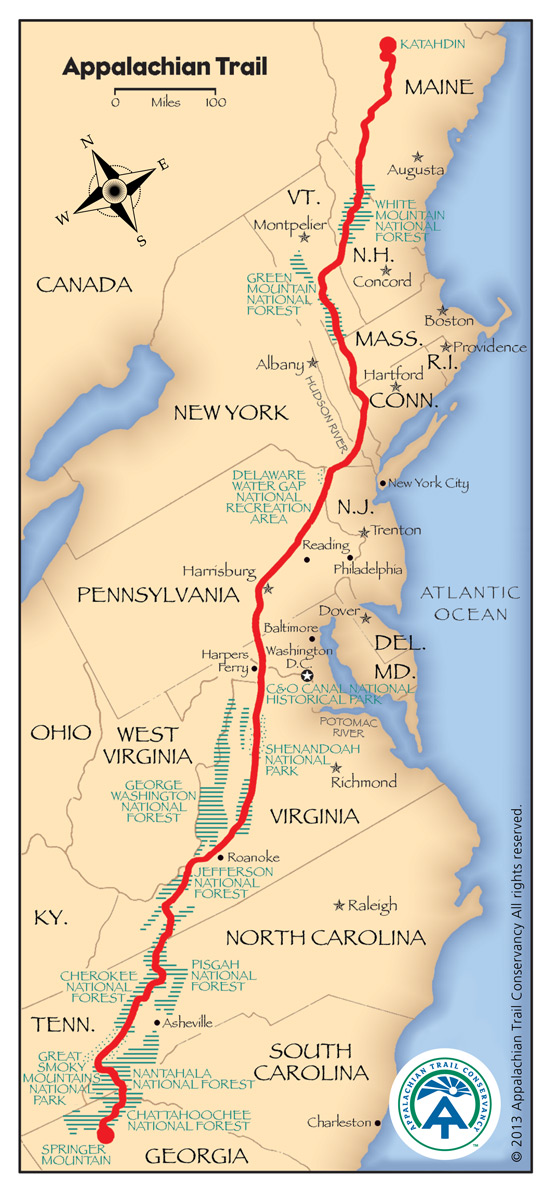

The Appalachian Trail is one of the longest continuously marked footpath in the world, measuring roughly 2,180 miles in length. The Trail goes through fourteen states along the crests and valleys of the Appalachian mountain range from the southern terminus at Springer Mountain, Georgia, to the Trail’s northern terminus at Katahdin, Maine.

Known as the “A.T.,” it has been estimated that 2-3 million people visit the Trail every year and about 1,800–2,000 people attempt to “thru-hike” the Trail. People from across the globe are drawn to the A.T. for a variety of reasons: to reconnect with nature, to escape the stress of city life, to meet new people or deepen old friendships, or to experience a simpler life.

The A.T. was completed in 1937 and is a unit of the National Park System. The A.T. is managed under a unique partnership between the public and private sectors that includes, among others, the National Park Service (NPS), the USDA Forest Service (USFS), an array of state agencies, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, and 31 local Trail-maintaining clubs.

Appalachian Trail Fun Facts

- The Trail is roughly 2,180 miles long, passing through 14 states.

- Thousands of volunteers contribute roughly 220,000 hours to the A.T. every year.

- More than 250 three-sided shelters exist along the Trail.

- Virginia is home to the most miles of the Trail (about 550), while West Virginia is home to the least (about 4).

- Maryland and West Virginia are the easiest states to hike; New Hampshire and Maine are the hardest.

- The total elevation gain of hiking the entire A.T. is equivalent to climbing Mt. Everest 16 times.

- The A.T. is home to an impressive diversity of plants and animals. Some animals you may see include black bears, moose, porcupines, snakes, woodpeckers, and salamanders.

- Some plants you may encounter include jack-in-the-pulpit, skunk cabbage, and flame azalea.

Hikers

- About 2 to 3 million visitors walk a portion of the A.T. each year.

- The A.T. has hundreds of access points and is within a few hours drive of millions of Americans, making it a popular destination for day-hikers.

- “Thru-hikers” walk the entire Trail in a continuous journey. “Section-hikers” piece the entire Trail together over years. “Flip-floppers” thru-hike the entire Trail in

- discontinuous sections to avoid crowds, extremes in weather, or start on easier terrain.

- 1 in 4 who attempt a thru-hike successfully completes the journey

- Most thru-hikers walk north, starting in Georgia in spring and finishing in Maine in fall, taking an average of 6 months.

- Foods high in calories and low in water weight, such as Snickers bars and Ramen Noodles, are popular with backpackers, who can burn up to 6,000 calories a day.

- Hikers usually adopt “trail names” while hiking the Trail. They are often descriptive or humorous. Examples are “Eternal Optimist,” “Thunder Chicken,” and “Crumb-snatcher”.

* Written by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy – Make A Donation

Appalachian Trail History and Important Dates

The notion of a “super trail” had been a parlor topic in New England hiking-organization and even academic circles for some time, but the October 1921 publication of “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning” in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects is almost universally seen as the moment of birth for the Appalachian Trail. Benton MacKaye—former forester and government analyst and newspaper editor, now intermittently employed as a regional planner—proposed, as a refuge from work life in industrialized metropolis, a series of work, study, and farming camps along the ridges of the Appalachian Mountains, with a trail connecting them, from the highest point in the North (Mt. Washington in New Hampshire) to the highest in the South (Mt. Mitchell in North Carolina). Hiking was an incidental focus.

The notion of a “super trail” had been a parlor topic in New England hiking-organization and even academic circles for some time, but the October 1921 publication of “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning” in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects is almost universally seen as the moment of birth for the Appalachian Trail. Benton MacKaye—former forester and government analyst and newspaper editor, now intermittently employed as a regional planner—proposed, as a refuge from work life in industrialized metropolis, a series of work, study, and farming camps along the ridges of the Appalachian Mountains, with a trail connecting them, from the highest point in the North (Mt. Washington in New Hampshire) to the highest in the South (Mt. Mitchell in North Carolina). Hiking was an incidental focus.

MacKaye immediately set about promoting his idea within his network of friends and colleagues in Washington, New York, and Boston, but it was again hikers who took up the cause—newspaper columnist Raymond Torrey in New York especially, who led a small crew building the first A.T.-specific miles in Harriman–Bear Mountain State Park under the aegis of Maj. William A. Welch, who soon shifted the goal to “Maine to Georgia” and designed the iconic diamond Trail marker.

By March 3, 1925, MacKaye and the Regional Planning Association had enough support to convene the first “Appalachian Trail conference…for the purpose of organizing a body of workers (representative of outdoor living and of the regions adjacent to the Appalachian range) to complete the building of the Appalachian Trail.” An organization of that name was formed, and Welch was named its first chair. But, building new trail and connecting to existing trails in New England did not follow to a significant degree for about three years, when a retired Connecticut judge, Arthur Perkins, and a young federal admiralty lawyer in Washington, Myron H. Avery, took charge of the efforts as a hiking-focused cause and MacKaye faded from an active role.

By March 3, 1925, MacKaye and the Regional Planning Association had enough support to convene the first “Appalachian Trail conference…for the purpose of organizing a body of workers (representative of outdoor living and of the regions adjacent to the Appalachian range) to complete the building of the Appalachian Trail.” An organization of that name was formed, and Welch was named its first chair. But, building new trail and connecting to existing trails in New England did not follow to a significant degree for about three years, when a retired Connecticut judge, Arthur Perkins, and a young federal admiralty lawyer in Washington, Myron H. Avery, took charge of the efforts as a hiking-focused cause and MacKaye faded from an active role.

Avery, especially after Perkins died in 1932, led a small corps of activists—eventually numbering perhaps 200—in identifying and blazing routes, establishing local clubs from Pennsylvania to Georgia, setting standards, publishing guidebooks and maps, and negotiating with national parks and other federal agencies. On August 14, 1937, the Appalachian Trail finally was on the ground, a continuous “wilderness” footpath of an estimated 2,000 miles from Mt. Oglethorpe, Ga., to Baxter Peak on Katahdin in central Maine.

A major hurricane, the Depression, World War II and its travel-limiting rationing all served either to break that continuity or retard efforts to achieve it again—a goal not reached until mid-1951, three years after Earl V. Shaffer, a Pennsylvania veteran “walking off the war,” reported to a disbelieving Avery that he had just walked the entire length in a single journey of less than five months.

A major hurricane, the Depression, World War II and its travel-limiting rationing all served either to break that continuity or retard efforts to achieve it again—a goal not reached until mid-1951, three years after Earl V. Shaffer, a Pennsylvania veteran “walking off the war,” reported to a disbelieving Avery that he had just walked the entire length in a single journey of less than five months.

While the end of World War II allowed the restoration of the A.T., it also triggered a vast wave of residential and highway development that threatened it anew. Almost half the Trail was still on roads and private property people wanted for vacation homes. In the early 1960s, Maine-born Stanley A. Murray of Kingsport, Tenn., who would become the ATC’s second-longest-serving chair, hatched with a small group of Maine and Washington, D.C., Trail veterans a campaign to both reenergize the organization (by sharply building up its base of individual members) and revive the idea of the federal government’s protecting of the Trail and its surrounding lands from adverse development. Both MacKaye and Avery had advocated such protection from the beginning, despite the volunteer origins of the whole project.

The campaign had its fits and starts, but, on October 2, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the National Trails System Act (NTSA), creating within the national park and forest systems a new class of public lands, national scenic trails—with the A.T. and the unfinished Pacific Crest Trail the first designated. States were encouraged to acquire lands for the A.T., and the National Park Service (NPS), with administrative responsibility for it all, and USDA Forest Service authorized do to so. The ATC soon hired its first two employees.

The campaign had its fits and starts, but, on October 2, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the National Trails System Act (NTSA), creating within the national park and forest systems a new class of public lands, national scenic trails—with the A.T. and the unfinished Pacific Crest Trail the first designated. States were encouraged to acquire lands for the A.T., and the National Park Service (NPS), with administrative responsibility for it all, and USDA Forest Service authorized do to so. The ATC soon hired its first two employees.

The latter and a few states jumped on the idea, but it, too, was not enough. In March 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed into law the ATC-generated NTSA amendments directing the federal agencies to move forward and authorizing almost $100 million from the Land and Water Conservation Fund for that purpose. The most complicated public-land acquisition program in history was begun, NPS formed an A.T. Project Office and special A.T. Land Acquisition Office, and the ATC led the way in securing the required annual appropriations—an effort now in its fourth decade and more than 99 percent complete.

Soon, the ATC’s primary functions of maintaining and protecting the Trail (including from the impacts of a surge in backpacking in the 1970s) and leading land-acquisition efforts had a third prong, perhaps its most challenging to date. It now had to manage, as a much larger national-park staff would, what would become more than 250,000 acres of public land, an estate with one of the greatest troves of natural and cultural resources in the entire national-park system. It accepted that role formally in January 1984 when the Department of the Interior delegated responsibilities to it for almost all management functions on the acquired lands.

Just as the backpacking surge meant developing new methods of designing and constructing durable trail, the new responsibilities meant growing the organization, developing new skills and programs, monitoring the Trail environment to provide data for biological scientists, and reaching out for more allies and to a new generation of Trail workers and Trail users. That has been the story of the ATC for the past quarter-century, reflected in the July 2005 change of its name to Appalachian Trail Conservancy, still volunteer-based.

IMPORTANT DATES IN APPALACHIAN TRAIL HISTORY

- October 1921 — An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning by Benton MacKaye appears in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects.

- April 1922 — Appalachian Trail Committee of Washington formed.

- March 3, 1925 — Appalachian Trail Conference established.

- January 1927 — Judge Arthur Perkins becomes acting the ATC chairman, stimulates additional field work.

- June 1931 — Myron H. Avery elected to first of seven consecutive terms as the ATC chairman.

- August 14, 1937 — Appalachian Trail completed as a continuous footpath.

- October 2, 1968 — National Trails System Act becomes law; A.T. becomes a national scenic trail under federal protection.

- August 1972 — The ATC headquarters moved from Washington, D.C., to Harpers Ferry, WV

- March 21, 1978 — “Appalachian Trail Amendments” to National Trails System Act signed into law.

- January 26, 1984 — National Park Service delegates to the ATC the responsibility for managing A.T. corridor lands.

- November 20, 2004 — The Board of Managers of the Appalachian Trail Conference overwhelmingly votes to change the organization’s name to Appalachian Trail Conservancy to better reflect its mission of preserving the trail experience for generations to come.

- July 4, 2005 — The Appalachian Trail Conference becomes the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, celebrating 80 years of caring for the Appalachian Trail.